Saturday, 23 January 2016

The Mithreum at Carrawburgh

I had the opportunity this weekend to visit the temple dedicated to Mithras on Hadrian’s Wall behind the auxiliary fort of Brocolita at Carrawburgh, Northumberland.

The remains of an early 3rd century mithraeum was discovered in 1949 and excavated by Ian Richmond and J.P. Gillam in 1950, and is the second-most northernly mithraeum discovered so far. The Brocolitia mithraeum is also the only sanctuary outside the Rhine provinces from which a monument of the goddess Vagdavercustis has been recovered. Like most other mithraea, the Brocolitia temple was built to resemble a cave, and also had the usual anteroom, and a nave with raised benches (podia) along the sides. At Brocolitia, the anteroom and nave were separated by a wattle-work screen, the base of which was found exceptionally well preserved.

The three altars found there were all dedicated by commanding officers of the unit stationed here, the First Cohort of Batavians, a Germanic people from the Rhineland. From left to right in the picture the named commanders are Marcus Simplicius Simplex (RIB 1546), Lucius Antonius Proculus (RIB 1544) and Aulus Cluentius Habitius (RIB 1545).

Mithraism is a Persian religion, with many aspects similar to another minor eastern Roman religion, Christianity, where the proponents are given the hope of a better afterlife rather than improving the current life and through this became a favourite of the Roman army.

Monday, 18 January 2016

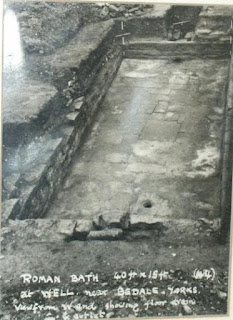

The Roman mosaic from Well

On my recent visit to Masham I had the opportunity to

photograph a Roman mosaic that I had wanted to see for a long time, but for one

reason or another never had. The pavement fragment from a villa and bath house complex

is located in the church in the nearby village of Well.

The corner fragment of mosaic that is preserved features

various classic designs of both guilloche and latchkey for the border and a

central geometric design that imitates cubes in 3d. It dates presumably from

the third or perhaps fourth century AD.

Sunday, 10 January 2016

The Temple of Aphrodite, Paphos, Cyprus

AE19mm, Augustus, Paphos, RPC I 3906

It’s been a long time since I visited the temple of Aphrodite at Palaeo Paphos, also known as Kouklia, on the island Cyprus, so much so that I can’t find the photographs that I took (back in October 2000). However a recent coin acquisition has taken me back there.The coin, of the emperor Augustus from the island of Cyprus, features the temple as its reverse design with, at its centre, the conical meteoric stone that was the main feature of devotion at the temple site.

The Histories of Tacitus record a visit by the emperor Titus to the site in the first century AD:

“While he was in Cyprus, he (Titus) was overtaken by a desire to visit and examine the temple of Paphian Venus, which was famous both among natives and strangers. It may not prove a wearisome digression to discuss briefly the origin of this cult, the temple ritual, and the form under which the goddess is worshipped, for she is not so represented elsewhere.

The founder of the temple, according to ancient tradition, was King Aerias. Some, however, say that this was the name of the goddess herself. A more recent tradition reports that the temple was consecrated by Cinyras, and that the goddess herself after she sprang from the sea, was wafted hither; but that the science and method of divination were imported from abroad by the Cilician Tamiras, and so it was agreed that the descendants of both Tamiras and Cinyras should preside over the sacred rites. It is also said that in a later time the foreigners gave up the craft that they had introduced, that the royal family might have some prerogative over foreign stock. Only a descendant of Cinyras is now consulted as priest. Such victims are accepted as the individual vows, but male ones are preferred. The greatest confidence is put in the entrails of kids. Blood may not be shed upon the altar, but offering is made only with prayers and pure fire. The altar is never wet by any rain, although it is in the open air. The representation of the goddess is not in human form, but it is a circular mass that is broader at the base and rises like a turning-post to a small circumference at the top”

Another interesting feature of the coin is that the reverse bears the name A Plautius, Proconsul. Michael Grant, in his book ‘From Imperium to Auctoritas’, suggests that this may be the father of Aulus Plautius, the conqueror of Britain and first governor of the province in 43 AD, leading his invasion in support of Verica, king of the Atrebates and an ally of Rome, who had been deposed by his eastern neighbours the Catuvellauni.

Saturday, 2 January 2016

A Vampire near Masham

Driving up a small valley outside of Masham in North Yorkshire the other day I came across a pair of severed wings with RAF roundels painted on them. I was curious as to the aeroplane type that had originally had them fitted so I grabbed a quick photograph.

I initially thought of a Canberra or perhaps a Meteor, however the curved fairing under the wing was wrong, plus the wheels on both of those aircraft point towards the fuselage whereas on these wings they point away. Then it came to me, the de Havilland Vampire. Sure enough the wheel alignment was correct and the visible fairing on the wing is from the tail boom.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)